by Lidia Paulinska | Mar 22, 2016

On Sunday, March 13, 2016, Fathom Events presented a live cinematic performance of “Spartacus,” the Bolshoi Ballet’s signature piece, viewed by fortunate movie-goers for one showing only in 500 cinemas worldwide. This epic ballet premiered in Moscow in 1968, marking the 50th anniversary of the October Revolution, and 48 years later it continues to exhibit all the energy, fervor, and raw brawn which has characterized the very essence of the Bolshoi’s male dancers ever since.

Staged by the legendary choreographer Yuri Grigororvich with an oddly cinematic but functional score by Aram Khachaturian, “Spartacus” is nothing short of spectacular in its display of space-devouring leaps and astonishing Olympic athleticism by its two principal male dancers: The incomparable Mikhail Lobukhin in the title role of Spartacus, leader of an unsuccessful slave revolt against the evil Roman ruler Marcus Licinius Crassus, powerfully performed by Alexander Volchkov. Both Lobukhin and Volchkov are the very personifications of the unbridled male energy and muscularity the Bolshoi has come to be known for, and accordingly, in the case of “Spartacus,” subtlety of expression is definitely not it’s strong suite. With successive decades and interpretations of this iconic work, we’ve come to expect nothing short of broadly expressed, passionate male heroism and this current production doesn’t disappoint; in the world of ballet, the role of Spartacus stands as the coveted tour de force piece for every principal dancer to aspire to.

Ably complimenting the merciless Crassus is his cunning and crafty courtesan, Aegina, performed seductively by the beautiful Svetlana Zakharova whose flowing, erotic movements contrast with the harsh, angular, war-like virility of the male dancers.

The fourth principal in this remarkable production is Anna Nikulina who plays the pure and virtuous Phrygia, wife of Spartacus, a role in absolute contrast to the vampish, glittering, and irrepressible Aegina. However, the contrast is so great, I feel Nikulina’s demeanor, and even her drab costuming depict her as a bit too bland, even considering her character’s “slave” status. Yet all is redeemed by her exquisite partnering with Lobukhin in their wonderful pas de deux, a breathtaking show-stopper with each successive lift more incredible than the former, and possessing a lyrical, subtle beauty so uncharacteristic of this muscular piece in general. The contrast works beautifully.

On balance, “Spartacus” is an historic treasure that has fortunately not become an historic artifact even after almost a half century. A dynamism prevails throughout, from the very first scene with Crassus in command of a gold-clad army, wielding shields and spears, dynamically lunge-jumping and forward leg kicking reminiscent of Fascism, to the horrific “crucifixion” of Spartacus in the final act, lifelessly impaled on the bloody tips of dozens of spears, held high above the heads of his victorious slayers. “Spartacus” intrigued us and held our attention.

by Lidia Paulinska | Mar 17, 2016

February, DEW 2016, Los Angeles – Margaret Czeisler, Chief Strategy Officer from Wildness, was talking about the characteristics of Generation Z. What the content creators and technology innovators need to know about that generation to serve better their needs?

What is unique about generation born after Millennials?

The age of the group is 21 and less. This is a generation that never has cable tv and they definitely had cut the cord or they are planning to do it. Generation Z lives in the times of fully embracing the social media – every minute 500 hours of videos are upload and shared to You Tube; half a million photos are upload to Snapchat. No wonder that 78% find branded or sponsored social media appealing, 77% find branded or sponsored You Tube videos appealing.

Generation Z is ready to rewrite the rules. They are transgender in the borders of gender, culture and race. It is not that they do not see race, but they are not judging on it – stated Czeisler based on her extensive research on Gez Z – They embrace differences in the way we have never seen in the past. Their approach to the culture is also very different and unique. They don’t consume the culture, they make it, create it. They are culture creators. They are catalysts of the culture revolution that we already experienced.

The opposite of Millennial, who hate failures and hide them, the Generation Z considers failure a natural part of living, an experience of life. Gen Z embraces the failure. (“Failure is a great thing. It teaches you what is good… what to do and what not to do. If you fail at this, then the next thing you know, you’ll find something else you can do better. You’re not going to fail at everything” – said Mira, 14). 91% of respondents said that failure is an important thing in life.

Gen Z is also well known as a generation of the shorten patience span.

by Lidia Paulinska | Mar 17, 2016

February, DEW 2016, Los Angeles – Digital Entertainment World is the conference that celebrates the visionary content creators and technology innovators who are creating the engaging products and experiences. But the key to successful outcome is to know the target group and its characteristics. Naseem Sayani, Vice President of Business Strategy from Huge presented to the audience the latest research on the generation of Millennials.

Who are the generation also known as “Generation Y”? How do we understand Millennials today?

There are no precise dates when this generation starts and ends; but most researchers use birth years from early 1980s to 2000. Sayani described them as the fearless generation. There is something the way they were raised that make them feel un-constrained by limitation or rules – she said – actually they set up their own rules and they have a passion around doing that. Often they disregard the instructions and do things their own way.

Sayani stated that Millenials are resilient in their pursuit of figuring out a system. There are no limits blocking their way. There is nothing that they can’t accomplish and nothing that cannot be done. They have grown up in the era of digital, not the transition from analog to digital. DVD was a standard, so they embrace You Tube naturally. They communicate through Snapchat and they are text savvy.

P.S. Let’s bring some other researchers founding of the Millennials characteristics on the top of Sayani presentation. Jean Twenge, the author of 2006 book Generation Me, attributes Millennials with the traits of confidence and tolerance but also identifies that they a sense of entitlement and narcissism. In 2008 Ron Alsop called the Millennials “Trophy Kids” That reflects a trend in competitive sports, where participation alone is frequently enough for a reward. Millennials have great expectations from the workplace so the employers are not necessary happy about them. They change their job frequently, always looking for something that is a better place and better salary. Sociologist Andy Furlong described them as optimistic, engaged, and team players.

by Lidia Paulinska | Mar 14, 2016

The redoubtable Metropolitan Opera of New York has done it again! A carefully crafted and finely balanced production of one of Giacomo Puccini’s twelve operas, Manon Lescault, a work in four acts composed in 1893, was offered for one night only on March 9, 2016 and shown simultaneously in 1,400 movie theaters in 50 countries throughout the world. It was an operatic gem not to be missed.

Puccini’s tragic love story is based on the 1731 novel L’histoire du chavalier des Grieux et de Manon Lescaut by Abbé Prévos. In 1884, a French composer by the name of Jules Massanet had written an opera titled Manon, and although based on the same novel, it has never reached the international acclaim as has Puccini’s work. In addition, another French composer by the name of Daniel Auber had also written an opera on the same subject with the title Manon Lascaut in 1883, but like Massanet’s work, it too is considered to be inferior to Puccini’s enduring composition.

The story deals with the urgency of young love and is the tragic tale of a beautiful young woman, Manon, who is ultimately destroyed by her conflicting needs for erotic love and a life of opulence and luxury. She is obsessively pursued by her young lover des Geieux for whom she yearns while being held captive by Gerona, a wealthy old lech who offers her a loveless life of luxury she willingly accepts. In the end, this conflict of desire leads to her loss of riches, love, and finally life itself.

Puccini’s Manon Lescaut premiered February 1, 1893 at Teatro Regio in Turin. It was Puccini’s third opera and his first great success. It was first performed in New York at the Metropolitan Opera on January 18, 1907 in the presence of the composer himself with Enrico Caruso in the role of des Grieux and legendary Arturo Toscanini conducting.

Puccini’s next work following Manon Lescaut was La Bohéme which premiered in Turin in 1896, conducted also by Arturo Toscanini and remains one of the most popular operas ever written. Puccini’s next work after La Bohéme was Tosca (1900) followed by Madama Butterfly which premiered at La Scala in 1904.

This latest Metropolitan Opera production of Manon Lescaut, brilliantly staged by the incomparable Sir Richard Eyre, was wonderfully accessible in a crisp, clean modern style, set as it was in 1941 Nazi-occupied France; it was magnificently balanced, melding voice, orchestra, costume and set design into one unified organic whole. The compact cast was perfect, featuring soprano Kristine Opolais in the title role and tenor Roberto Alagna as her distraught lover des Grieux. The leads were ably complimented by baritone Massimo Cavalletti as Manon’s protective brother Lescaut, and the ever-villainous bass Brindley Sherratt as the lecherous old Gerona. The Met’s Principal Conductor Fabio Luisi expertly lead the stirring score.

This was a production not to be missed and through the unfailing production expertise of Fathom Events, it was made available to be enjoyed by audiences world-wide.

by Lidia Paulinska | Mar 9, 2016

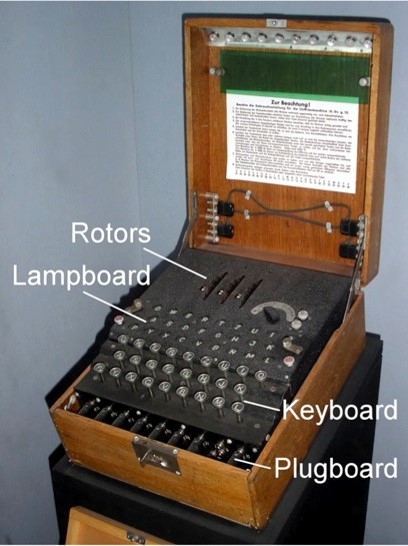

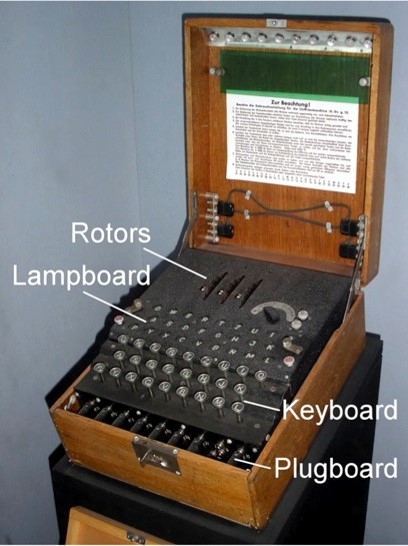

March 2016, RSA, San Francisco – After hours spending on the show floor at RSA conference and the talks about security, vulnerability, encryption and authentication I stopped at the Gemalto booth in the North Hall of Moscone Convention Center to listen the presentation. Scott Meltzer from Gemalto was talking about the history of famous encrypting machine Enigma. The company also presented the real 1946 original Enigma machine (NEMA) at the booth. That was a Swiss, 4-rotor model with a movable reflector, built for the Swiss Army in 1946. 1 of 300 machines that are known to still exist today.

Here is the story that was presented.

The most common information that we hear about the Enigma code is that it was super-secret throughout WWII, and it took one man to invent but over 10,000 men to defeat.

Well, none of it is true.

The Enigma was invented in 1918 by Arthur Scherbius in Germany. The inventor was highly interested to share his “rotating rotors” encryption machine with the military but the WWI was just about to end and army wasn’t interested. So, instead he put his invention for commercial use and started the company. The first prototype called Enigma A came to life in 1923. Enigma D, the first commercial version, was produced in 1927 and sold in multiple countries to encrypt financial information, diplomatic communiques, and military messages. By 1928, both German Army and Navy were using customized and upgraded versions of those machines. In fact, the British government had actually purchased several first generation Enigma machines back in 1926.

So, what is the Enigma machine and how it works.

It’s a huge polyalphabetic substitution cypher. Each message is encrypted with its own unique key. Keys are around 17,000 characters long. There are non-repeating substitutions and no easily discernable pattern. The sender would press a key on the keyboard. This would advance the first rotor one step and send an electric signal from the keyboard, through the plug-board. This would be the first substitution in the cypher. Each rotor then introduced an additional substitution as that signal went through it. Another substitution at the reflector and then back through the rotors in reverse and out through the plug-board, with additional substitutions at each step. And finally the signal was sent to the lamp array to show the encoding of that letter. The genius of this electro-mechanical system was that the encoding was reciprocal. If you typed a “W” on one Enigma, and it came out a “B,” typing that “B” on another Enigma would reproduce the “W,” but only if their initial settings were the same. And because a rotor would move every time a key was pressed, the circuit created by the next key pressed would be completely different than the previous circuit and would generate a completely different substitution.

The Enigma was the most powerful and unbreakable code machine. Until 1932.

Just before Nazis came to power, three Polish mathematicians: Marian Rejewski, Jerzy Rozycki and Henryk Zygalski, successfully broke the Enigma. Poles were able to decrypt 75% of the German army’s Enigma-encrypted radio transmissions between 1933 and 1938. But once the war began in 1939, the Nazis upgraded their machines. They distributed 2 additional rotors, and they changed their procedures to plug several security holes that the Poles were exploiting. This didn’t stop the Poles from breaking some of the Nazis’ daily codes, but each success took much longer, and breaking the entire system would have required way more manpower than they had. They also knew from some of their decrypted messages that Hitler had set his sights on Poland and was planning his move within the next 6 weeks. So, five weeks before Nazis invaded, the Poles gave French and British codebreakers all their information, including working models of the Nazi’s military Enigmas they had reverse-engineered, along with the Cyclometers, Bombas and Zygalski decrytping sheets they used to decode them.

And this is when the more familiar story of breaking the Enigma code begins.

The story of The Bletchley Park Team – Dilly Knox, John Jeffreys, Peter Twinn and Alan Turing, along with over 11,000 others started to deliver their Ultra decrypts. “It was thanks to Ultra that we won the war” – said Winston Churchill to King George VI. BBC claimed that this team shortened the war by at least 2 years. The story was recently portrayed in the movie “The Imitation Game” starring Benedict Cumberbatch and Keira Knightley.